The harm & hypocrisy of AI art

“How easy it is to create and maintain the illusion of understanding, hence perhaps of judgement deserving of credibility... A certain danger lurks there.”

(Disclaimer: The views expressed here are my own personal opinions, and not those of Sony Interactive Entertainment)

For anyone who works in tech, generative artificial intelligence (AI) has been the hot topic of the last couple of years. We’ve seen an explosion of interest around the tech world, with companies big and small scrambling to adopt AI tools and weave AI features into their software. Everyone is seemingly terrified of missing out on what we’re told is the next big thing; even Photoshop - the old reliable friend of graphic design - includes AI tools, now. Stories appear daily about how AI will change society and propel us all into a brighter future, their writers proclaiming a raft of utopian assertions from the end of poverty to making everyone an artist.

I’ve started to see AI image generators and other tools popping up with startling frequency in the daily work and discussions I have with my peers. Engineers ask ChatGPT to write code, managers use Midjourney to fill their PowerPoints with bespoke images, and even designers ask Dall-E to create UI concepts for them. Nearly everyone seems awed by the novelty and magic of this new toy, and I often hear the same mantra - everyone’s job will soon rely on this. Embrace it, or risk being left behind.

UI mockups auto-generated by Midjourney. Source: https://t.ly/B6HlH

So I started digging into both how AI works, and what impact it’s having, particularly on the creative industry I’m proud to be a part of. This article has been a long time coming for me. The more I’ve learned, the more I’ve become first alarmed, then angry, then compelled to speak out. As a designer in the tech world, I want to put forward a different view to one we usually hear, and to explain clearly why I for one, am appalled by the arrival of AI.

AI in 2024

Machine or deep learning models - that which we now brand AI - have been around in a basic form since the 1950s, but thanks to recent advancements in GPUs, have made a huge leap forward in capacity. What separates AI from say, the cloudy metaverse visions of last year, is that AI is already shipping and impacting our lives for the worse - even if it’s not quite the stuff of everyday pub debate.

Using generative AI tools like ChatGPT, and Stable Diffusion, people can type a request into a browser in straightforward English, and get back a whatever they asked for - be that a recipe, an illustration, or even a faked photo or video. With gadgets like the Humane AI Pin, people can also do the same by speaking out loud, in a manner reminiscent of the sci-fi movie, Her.

The Humane AI Pin. Source: https://shorturl.at/qWZ58

When using an AI generator the images and articles that come back are often uncanny and strange, but still strikingly realistic - good enough to pass for something written, painted or photographed by a real person. Yet it’s in the details where they still fall over - at least for now - showing hands with seven fingers, writing repetitive prose, or drawing what should be text as gibberish symbols. Despite the limitations, the appeal of cheap, instantly available art and writing holds obvious appeal for the commercial world, and AI companies have quickly amassed colossal profits. OpenAI for example, making an incredible $1.6 billion last year.

How it works

What we call AI today is nothing like the sentient robots of sci-fi movies - an ‘AI’ is a mathematical model, written in computer code, that is good at spotting patterns and correlations in data. In most cases, ‘data’ means a big pile of text or images - millions of photos or online articles, for example. AI companies can feed their models huge libraries of photos or books, and by analysing everything it’s fed, the model can then generate its own versions which look pretty close to the real thing. At first the model is likely to produce complete garbage, but through a trial and error process can be ‘trained’ by an engineer to generate some impressive results.

The sample image Stable Diffusion currently use to introduce their AI tool. Source: https://shorturl.at/kuvFH

Training a model requires a vast amount of ‘data,’ and also comes at a not insignificant cost in terms or energy, carbon emissions and human labour. All that ‘data’ has so far mostly been scraped from the internet - taken in secret from people who didn’t know and didn’t consent to handing it over.

Low-paid workers are used to manually filter offensive and upsetting images out of the datasets, and to type out description tags for the millions of images, so that the machine knows what its looking at. Programmes like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk - which pays a pittance to people for each image they tag - hides struggling workers behind a curtain whilst giving the impression of a shiny, automated front-end.

Source: https://www.smbc-comics.com/comic/rise-of-the-machines

What AI can and can’t do

Everything an AI is fed must first be categorised and converted to numerical data, in order to be consumed. There is a process of abstraction and reduction that must happen, turning a digital image into a numerical matrix of RGB pixel colours and positions. This abstraction means a whole lot of nuance, detail and context that we understand as humans - anything that can’t be easily quantified - is lost as data is fed into the machine. The Mona Lisa becomes just more numbers in the pile.

AI will also amplify any inherent bias in its training dataset. For example, if a model is trained on a police database and told to suggest jail sentences in a courtroom - something which is already happening in the US - it will have inherited any racial bias that was present in the records of arrests, and be more likely for example, to suggest harsher sentences for black defendants. Famously too, if one prompts Dall-E with the word ‘CEO,’ it will only produce images of white men.

AI models are highly dependent on the input dataset - what it contains, what’s conspicuously absent, who curated it and to what end, all affect the results. Without any governance whatsoever, that means Silicon Valley tech companies get to decide exactly which way the models lean and what they do - and the more widely AI is used, the more their particular world view and biases propagate.

The process of training an AI model on vast quantities of input data

Source: https://forbytes.com/blog/ai-models-explained

When someone asks the machine to generate an image, the model scans over everything in its dataset and makes a calculation - out of everything it has, which combination of colours, shapes and lines best fits the request? It’s a mathematical brute force approach, not unlike the classic adage of infinite monkeys at typewriters - feed the AI enough data and it will eventually give you something about right. The machine doesn’t draw or paint - it can only break down its dataset into billions of parts, and recombine them to deliver mash-ups of what came before, as strange and uncanny as they may be.

In this way, an AI model is technically incapable of producing anything new. It’s limited view of the world is based entirely on the abstracted number set it was given. An AI model amazes only because it has devoured so much raw material, to remix at your behest. As clever as it may be at spotting patterns, it cannot adapt, interpret or imagine like a human being can. What it can do very well however, is copy an artists’ style or fake a photo with disturbing accuracy.

Illustrations by artist Hollie Mengert (left) & AI output based on her stolen work (right)

Source: https://thealgorithmicbridge.substack.com/p/why-generative-ai-angers-artists

Entirely AI-generated fake photos - alarmingly difficult to tell from the real thing

Part of the branding exercise around AI tools has been about building mystique. AI enthusiasts talk about its limitless potential to transform society for the better, by taking over more and more decisions for us. There is an almost religious zeal for this in some quarters, from which predictions flow of utopian futures where all problems are solved through learning to embrace the wisdom that flows from these machines; but as we’re seeing, these machines are far cruder and more flawed than the hype suggests.

“Generative AI is the key to solving some of the world’s biggest problems, such as climate change, poverty, and disease. It has the potential to make the world a better place for everyone”

One aspect of AI’s working which perhaps fuels these beliefs, is the opaqueness of its decisions. As models are trained, they make myriad correlations and connections which are never fully visible to the engineers. Whilst not truly a ‘black box,’ models nevertheless produce output without us fully knowing what’s going on inside. This lack of accountability means it would be unforgivable to say, trust them with decisions that affect people’s lives. By the same token, the box of mystery can appear as if magical - the machine really looks like it’s thinking and understanding, prompting some to proclaim that in time anything is possible. AI is not intelligent, however. It blindly connects and calculates, no matter how misguided or illicit the task.

For now, AI-generated images can be spotted via the mistakes they make with fine details - such as human fingers - but we can expect this to change

Source: https://t.ly/HPduD

“Generative A.I. art is vampirical - feasting on past generations of artwork even as it sucks the lifeblood from living artists. Over time, this will impoverish our visual culture.”

The Vampire Machine

It’s important to understand that OpenAI (creator of Dalle-E), StabilityAI (creator of Stable Diffusion) and Midjourney - the big three image generators - all trained their successful models by scraping millions of other peoples’ images from the internet - apparently entirely without the owners’ knowledge or permission. Lawsuits surrounding this are still ongoing.

This is worth reiterating: The billion-dollar-making generators we see today appear trained on the copyrighted works of far poorer artists, illustrators and photographers; taken directly from their portfolios and community sites like DeviantArt. This is copyright infringement on a completely unprecedented scale, and in my opinion corrupt, cynical and immoral. Paying users can even directly prompt the image generators to produce artwork in the style of an artist by typing their name - making no secret of the fact that their work was absorbed by the model.

‘Dragon Cage’ by artist Greg Rutkowski (top), whose name has been used tens of thousands of times as a prompt in Stable Diffusion to generate lookalike images (below).

Source: https://www.businessinsider.com/ai-image-generators-artists-copying-style-thousands-images-2022-10?r=US&IR=T

Only because this has never happened at such scale and speed before, has the law been slow to respond, and the AI companies so far have got away with it. Much like Uber, it seems they knew that if they moved fast and broke things, they could make their money and be established before the law caught up with them - whilst claiming to disrupt and innovate for the common good. It seems some in Silicon Valley have claimed the right to appropriate artists’ work in order to mechanically process it, and sell it back to us.

“All that we’ve been working on for so many years has been taken from us so easily with AI... It’s really hard to tell whether this will change the whole industry to the point where human artists will be obsolete. I think my work and future are under a huge question mark”

Following the outcry from the many artists whose work was used, OpenAI and Midjourney are now facing copyright infringement lawsuits from the likes of Getty Images and the New York Times. AI companies thus far seem unrepentant, which is perhaps unsurprising given the profits they’re making.

Democratising art

The big three image generators claim some noble and lofty goals whilst making their money off of others’ work. Midjourney for example, claims to be “expanding the imaginative powers of the human species” whilst StabilityAI say they are “building the foundation to activate humanity’s potential.” The story sold to us is similar across the board - that art is being ‘democratised’ - pulled from the clutches of those entitled artists and mechanised - converted into a tool that will instead make everyone an artist.

By its fans, ‘AI art’ is often described as a new medium or frontier, where humans forgo the effort of making their own art or building any skill - instead pushing buttons to have art appear instantly. Rather than discovering the joy of creating, we’re told instead it’s better we learn to think as the computer thinks, and become experts at writing prompts because, hey.. it’s the same thing.

‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’’ by Pablo Picasso. A painting which disrupted modern art without hurting artists. Source: https://t.ly/zIiLI

By its nature, art has always been something society struggles to firmly define, and that makes any discussion around its definition difficult. As soon as we establish a common idea of what constitutes art, an artist like Picasso or Duchamp is compelled to push the boundaries - making it an ever evolving and expanding field.

But ‘AI art’ is something very different. Boundary-pushing art never threatened the careers of other artists before, or threatened to monopolise the means of creation - it simply challenged our ideas about ourselves and our world. New art might shock us or make us uncomfortable, but it’s never had this much destructive power, nor generated this much money for a handful of men so quickly.

“Everyone is looking for the hack - the secret to success without hard work”

Art and illustration is everywhere in our world - it captures our imagination on book covers, brightens our homes, brings magazine articles to life, and adds richness to the environments of video games. The artists who create all of this are the under-appreciated workforce that breathe life and meaning into our everyday. They love their work, spend their entire lives honing their skills, and are often short-changed considering the value they give their employers. They’re expected to produce exceptional art to ever-shrinking timescales for often mediocre money. But they do it anyway, because this is what they love - bringing beauty and soul to the world.

A piece by Mario Klingemann. Producing images with AI image generators, Mario describes himself as a full-time “AI artist.” Source: https://t.ly/53-mv

Over the last two years, commercial adoption of AI image generators has meant that real illustrators and artists are losing paid work and control of their own images. Now, the companies who would have previously hired artists can turn to a cheap, mechanical equivalent, and as long as this option is available some won’t be able to resist. AI images may be inferior in the details, but they’re incredibly cost efficient and near instantaneous. Automating this is about seeing art as simply ‘content,’ and what matters is that it keeps coming quickly and cheaply. Someone can be hired to touch-up any problems with the images at far less expense to the company. These workers are also lower skilled, disempowered and more interchangeable than they were before.

This type of automation is a common corporate path. People don’t necessarily lose their jobs, but algorithmic management instead takes away their power, and lowers their pay and protections.

Far from ‘democratising’ art, AI tools are instead having the opposite effect - privatising and automating it. AI is pushing skilled people out of the process and handing control to a handful of tech companies in a race to reduce and commodotise.

‘House of Earth and Blood’ by Sarah J. Maas. Publisher Bloomsbury used an AI-generated stock image for the book’s cover. Source: https://t.ly/smdNo

The entirely AI-generated title sequence to Marvel’s ‘Secret Invasion’ TV show. Source: https://t.ly/qFjR8

Videogame art assets, automatically generated with AI, instead of created by a game environmental artist. Source: https://shorturl.at/kARXZ

Art is intrinsically human

To call AI-generated images equivalent to real art, is - in my opinion - to entirely miss the point. The effortless, instantaneous nature of AI generation prevents it from having real meaning. It’s disposable. AI companies truly misunderstand art in thinking that the image is what matters, rather than the intent and the labour.

Art has always been intrinsically human. It comes as much from our flaws and mistakes as it does our successes. Through the process of making it, we express what’s inside us - our joy and frustration, longing and sadness - in a way which is instinctive and deep-rooted. It’s only through experiencing life as human beings that we have something to express and put to canvas or page. More often than not, we discover what the artwork is to be through the process of creation, rather than having a firm vision at the outset and simply assembling it, as a machine does.

We all know it when we see it - that painting that holds our attention or music that speaks to us. Through the sweat and the hours they put in, the artist communicates those feelings to us, the viewer, and that’s part of the joy of engaging with art. We feel understood and more connected as human beings as a result.

Photo by Ari He. Source: https://t.ly/3XFiS

Take away that substance, and what do you have? A lifeless matrix of pixels. With AI art, there is no feeling to communicate, no creative process, and therefore no value imbued in the ‘content.’

As any designer knows, the act of making art is also a way of observing, thinking and problem solving. The creative mindset is something which must be exercised, and which can be applied in so many other areas of life. It’s at the heart of all design and architecture. By letting a machine think for us, we are robbing ourselves of the joy and reward of creation.

AI models are an inherently conservative technology. By thinking on your behalf, and by reducing creative decisions to an algorithmic, wholly quantitative process, they severely constrain the possible outcomes, and no true artistic surprises or discoveries are possible. The models simply crunch the data they’re fed and serve a mash-up back to you. Nothing more.

The inevitability myth

But - AI enthusiasts have often told me - now the genie is out of the bottle, it' can’t be put back in. We should adopt AI or be left behind. The idea that we should fight to help destroy a vital part of our society’s culture so corporations can benefit, is deplorable to me. There’s nothing inevitable about technological change. Any development takes time, effort, money and determination, as well as a clear intent - continuously reinforced so that a team of people can work towards a common goal.

Technological change is a political and commercial process, shaped by the interests of the corporations and governments that surround us, who make deliberate and resolute choices. So the AI tools we have today are a choice, and a different choice can be made at any time. If we want to see AI work differently, or even pull the plug altogether, we can collectively do so.

Source: https://shorturl.at/dizYZ

One has to wonder - when we could use AI models for so many different purposes, why try to automate illustration, and not something we’d all much rather not do, like tax returns? As artist Molly Crabapple said: “I cannot understand why someone would burn a tonne of carbon, just to take away a job people love to do, and give it to a machine.” It’s entirely possible that Silicon Valley tech men just thought they were tinkering with an interesting maths challenge, and didn’t think what the consequences might be for other people. Perhaps these engineers share a reductionist world view, where the human brain is seen as a computer, and everything in life can be expressed through equations and code. Heartbreakingly, perhaps this even extends to art.

Photo by Ivan Samkov. Source: https://shorturl.at/clEIN

The long term impact

If we continue on the path AI tools have set, then creative careers such as illustration and journalism will be far less viable, and far fewer young people will enter the creative fields. They may disappear entirely.

Art is often undervalued today, but by automating it we drive that appreciation even further down. Art would be regarded as something that can be produced instantly at scale, and more worryingly, given precious little thought or effort.

We’d have fewer artists, writers or musicians, and those we do have will be from the same wealthy, privileged segment of society. That narrowing of experience means any real art we get will be all the poorer, and with fewer people able to spend their time creating art, we can expect less evolution and growth of the field. There’d be no more Grayson Perrys or David Bowies. Art may ultimately become regarded as something machines do, not us - which is backwards and perverse.

“As we invent more species of AI, we will be forced to surrender more of what is supposedly unique about humans. Each step of surrender—we are not the only mind that can play chess, fly a plane, make music, or invent a mathematical law—will be painful and sad.”

As AI-generated images fill the internet, there will be less real art to train the models on, so if demand keeps growing, we can expect them to be fed more AI-generated images instead. It’s easy to see where that leads - a steady degradation of quality as copies are copied over and over again, and the richness of the original work fades from memory. AI art is ultimately a race to the bottom.

Whilst the AI companies claim to be taking us towards the future, I for one find their vision to be cynical and cold. Follow this through, and it leads to a world where humans express creativity only through a corporate-owned platform which we pay for on a monthly subscription. Do we really want the means to create art to be taken and privatised? This is the direction we’re headed, unless we decide to say no.

The fight back

All of this is rather depressing - and it should be - but there is good news, too. Many people aren’t taking this lying down, and a strong and steadfast call for change is growing by the day.

At the grassroots level, professional artists and illustrators have been staging protests by filling community sites like DevinatArt and ArtStation with a tidal wave of protest placards. In addition, many of the companies that produce the software and sites creatives use, have found themselves needing to clarify their stance in the face of widespread unrest. Where companies have always claimed to be supportive of artists, now they’re being asked to prove it through their actions - by for example, banning AI art from their sites.

Simultaneously, New-York based illustrator Molly Crabapple has posted an open letter and petition, calling for book and magazine publishers to take a stand with artists and refuse to use AI art. Letters like this have become focal points for thousands of supporters, and Crabapple’s includes signatures from high profile people such as author Naomi Klein and actor Jon Cusack.

But some artists have been brave enough to take their challenge all the way to court. After discovering that her work has been used to train AI models without her consent, concept artist Karla Ortiz - along with two other artists - is driving a class-action lawsuit against StabilityAI, Midjourney and DeviantArt. Their legal challenge cites copyright infringement, unfair competition and reputational harm. Karla’s fight has helped bring public attention to the plight of artists and raise awareness about the real human impact of AI.

“If we’re going to talk about what really stops people from pursuing art, it’s those economic issues. It’s issues like a lack of universal health care, few meaningful grants for artists, and the fact that most of us are just a missed paycheck away from homelessness and hunger. This doesn’t solve that.”

Illustration by Karla Ortiz. Source: https://shorturl.at/avCX1

At the time of writing, big players such as The New York Times and Getty Images have also launched their own lawsuits, adding significant weight behind the call for justice. With all this mounting pressure, it seems unlikely that image generators will be able to continue as they have been for much longer.

Last year, an art competition at the Colorado State Fair was unwittingly won by an Midjourney-generated image. Jason Allen, the man behind it, only admitted using AI after he had won the competition, and was subsequently disqualified. Nevertheless, he contested the decision amid heated debate over what constituted both ‘art’ and ‘artist,’

Around the same time, a man named Stephen Thaler tried to get US copyright for an image he produced with AI which he called ‘A Recent Entrance to Paradise.’ In court, he argued that an AI model should be granted a copyright because we’ve been using mechanical devices like cameras for years. He didn’t convince the federal judge however, who ruled that "human authorship is an essential part of a valid copyright claim."

I firmly agree with that judge. Whilst artists regularly use different devices to produce art, they are always the source of imagination and skill, and always directly controlling the tools. With AI art, the user is no longer in any real control of what comes out, and so should not be considered its author.

‘Théâtre D’opéra Spatial’ - made by Midjourney from a prompt by Jason Allen - which contraversially won first prize in the 2023 Colorado State Fair art competition. Source: https://shorturl.at/fhkow

‘A Recent Entrance to Paradise’ - made by AI from a prompt by Stephen Thaler - who tried and failed to win a copyright issue for the machine as an author. Source: https://shorturl.at/eoALO

Copyright law, design registration and similar legal frameworks exist to protect the livelihoods of creatives. They’re old and far from perfect, but nevertheless deserve to be protected. Copyright law reinforces the value of their work and ensures artists - many of whom are self-employed - get some small amount of pay when sick or something in retirement. If AI can just ignore copyright law, then it can take away what little income protection artists have.

Art software giant Adobe are now attempting a more ethical take on generative AI with Firefly. Targeted at creatives, Firefly claims to retain an evidence trail linking results to the original input images, though how well this will work is still unclear. Adobe and others are also trying to establish some governance with a universal ‘Do Not Train’ tag which might protect artists’ work from being scraped by AI models. One has to ask though, why the onus should be on the artists to enforce protection, rather than reigning in AI in the first place.

Firefly - Adobe’s first attempt at a more ethical image generator. Source: https://t.ly/mxNZq

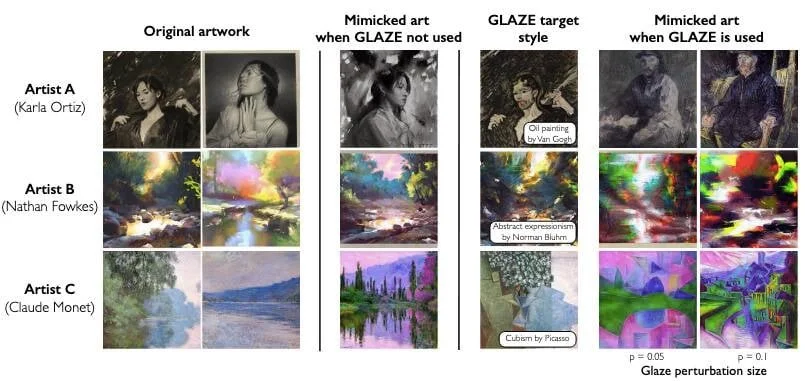

Another way artists can protect their work is with Glaze. A software tool created by a team at the University of Chicago, Glaze allows artists to invisibly encrypt their digital artworks to prevent AI models using them.

Whilst the images remain unchanged to the human eye, they will now completely confuse AI models attempting to train on them. It’s an active digital watermark that just might afford creatives some genuine protection and peace of mind whilst the legal and commercial worlds struggle to catch up.

Glaze offers artists protection against unwanted scraping by AI models

Source: https://shorturl.at/apvL3

Constructive criticism

I’m never one to just complain without offering a better suggestion, so the last thing to address is - what’s a more positive way forward?

Ideally, I would love to see AI image generators disappear in their current form. I’m a designer, and the reason I became one in the first place was to make technology revolve around people. If we don’t know how something will benefit people, then why should we bring it into the world in the first place? If it actively harms people, then we should stop immediately, and rethink what we’re doing. That’s why I’d like to see these tools rethought by people with a stronger understanding of the impact on working artists.

The money and resources put behind AI tools today could be redirected towards goals that really benefit society. It would be encouraging to see a human-centric exploration of how AI could be put to better use and to have the outcomes thought through, prototypes trialled and communities’ feedback sought, before anything is launched.

I would like to see copyright law updated and reinforced to tackle this new type of problem, with a focus on protecting the livelihoods of working artists, and recognition of the value their art brings to society. Hopefully the lawsuits happening at the time of writing will set a precedent for this and lead to greater legal protections.

I learned recently that Stable Diffusion allows people to train their own custom AI models using their own training datasets. If people were legally required to own or have permission to use all the data they put into models, that would certainly be a step in the right direction - perhaps by requiring companies to keep copies of the original datasets - though this alone would not undo the damage that’s already been caused.

Photo by Elena Mozhvilo. Source: https://shorturl.at/sxGN8

A wonderful legacy

But above all else, perhaps this drama could remind us all of the value of art and how it enriches our lives. We’re coming precariously close to destroying something that in no small part makes the world a place worth living in, and enables society to function through expression, reflection and connection. We’re lost without art, and we cannot afford to take it for granted.

What if we all decided to say no to AI, and instead worked up the courage to try and draw, or paint, or sculpt by ourselves? What if the strange, artificial taste of ‘AI art’ left us dissatisfied, and curious enough about creativity to start doodling with a biro in our notebook? It might feel good, and it might spark a flicker of creative confidence. After all, we all drew as children, but as we’ve got older, we’ve forgotten how.

What a wonderful legacy AI art might have, if it disappeared and made all of us into artists. Artists who need nothing more than pencil, paper and our own feelings as inspiration. We had everything we needed, all along.

Further reading & listening

Podcasts

Why AI is a Threat to Artists w/ Molly Crabapple : Tech Won’t Save Us Podcast, Episode 174

AI Criticism has a Decades-Long History w/ Ben Tarnoff : Tech Won’t Save Us Podcast, Episode 182

The Human Side of the AI Underclass w/ Joanne McNeil : Tech Won’t Save Us Podcast, Episode 196

The Future of the State w/ James Plunkett : Jon Richardson & The Futurenauts, Season 3, Episode 4

Books

Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech by Brian Merchant

Resisting AI: An Anti-Fascist Approach to Artificial Intelligence by Dan McQuillan

Hello World: Being Human in the Age of Algorithms – Hannah Fry

Articles

AI-Generated Art Controversy: The Future of Creativity or a Replacement for Human Talent? by Adam Hencz for Artland

Restrict AI from Publishing: An Open Letter by Molly Crabapple for The Center for Artistic Inquiry and Reporting

Independent Artists Are Fighting Back Against A.I. Image Generators With Innovative Online Protests by Richard Whiddington for Artnet

Molly Crabapple Has Posted an Open Letter by 1,000 Cultural Luminaries Urging Publishers to Restrict the Use of ‘Vampirical’ A.I.-Generated Images by Jo Lawson-Tancred for Artnet

No, teaching AI to copy an artist’s style isn’t ‘democratization.’ It’s theft by Soleil Ho for The San Fransisco Chronicle

Stability AI swerves copyright infringement allegations in response to Getty lawsuit by Tim Smith and Kai Nicol-Schwarz for Sifted

Glaze protects art from prying AIs by Natasha Lomas for TechCrunch

US judge: Art created solely by artificial intelligence cannot be copyrighted' by Jon Brodkin for ArsTechnica

The US Copyright Office says an AI can’t copyright its art by Adi Robertson for The Verge

Weizenbaum’s Nightmares: How the inventor of the first chatbot turned against AI by Ben Tarnoff for The Guardian

AI Machines aren’t ‘hallucinating,’ but their makers are by Naomi Klein forThe Guardian

How Adobe is managing the AI copyright dilemma, with general counsel Dana Raoby Nilay Patel for The Verge

Why Generative AI Angers Artists but Not Writers by Alberto Romero for The Algorithmic Bridge

AI: Digital artist's work copied more times than Picasso by Clare Hutchinson & Phil John for BBC News

This artist is dominating AI-generated art. And he’s not happy about it by Melissa Heikkiläarchive page for MIT Technology Review

Artists slam Marvel over AI-generated credits in Secret Invasion by Mark Sellman for The Times

Courts are using AI to sentence criminals. That must stop now by Jason Tashea for Wired

The New York Times is suing OpenAI and Microsoft for copyright infringement by Emma Roth for The Verge

Getty gets tough on London-based AI firm by William Charrington and Hoi-Yee Roper for Farrer & Co